|

|

Proceedings of the Known World Dance Symposium 2007 |

Reconstruction Techniques for Dance

Craig W. Shupeé

(Master Philip White)

Introduction

Beyond learning dances by rote, you can learn how dance steps and choreographies are derived. This will improve your sense of style and technique as a dancer and your methods of instruction as a teacher. An examination of primary source material initiates the comprehension of how extant dance steps and choreographies are transformed into performable dances. This paper analyzes the importance of facsimiles, transcriptions, translations, tabulations, and concordances in the reconstruction process. Their significance is applied through detailed techniques to specific dances of Renaissance Europe. A firm understanding of most European Renaissance dance styles will allow you to benefit from the full potential of the reconstruction techniques.

The fundamental techniques you learn from this paper should assist you in the reconstruction of both dance steps and the choreographies that use them. It is as important to recreate the movement as well as the choreography. By reconstructing these steps, you will only aid your understanding of dance. However, the reconstruction of dance steps is often more challenged and debated than the reconstruction of choreography. This is mainly because step descriptions use a broader range of language, which could be misinterpreted in translation. For this work, choreographies are used as examples of reconstruction techniques, rather than dance steps, to make their function of the techniques as unambiguous as possible.

Working only from a facsimile of a dance is possible but often difficult to form a direct and accurate reconstruction. Aside from being a difficult proposition, facsimiles generally contain errors and lack consistent arrangements. This challenge of dancing directly from a facsimile can be entertaining but also overwhelming. For some, the trial of reconstructing is, in itself, a daunting task. These reconstruction techniques described below are designed to reduce the reconstruction process into its most basic steps to help even novice dancers gain experience in reconstructing. After reconstructing several period dances, I began to formulate a general set of techniques which can be used on a wide variety of dances. I have condensed these techniques into a step-by-step procedure for use by others. This procedure is presented here.

Terminology

The following terms are defined so that our working vocabulary concerning reconstruction is the same. These definitions come from www.dictionary.com.

Term Definition

Choreography A work created by the art of producing and arranging dances.

Comparison Examining resemblances or differences; relation based on similarities and differences; qualities that are comparable.

Concordance A topical index or orderly analysis of the contents of a dance.

Facsimile A copy of anything made to give every part and detail of the original; an exact copy or likeness.

Modify To change somewhat the form or qualities of; to alter somewhat; to limit or reduce in extent or degree; to moderate; to qualify; to lower.

Reconstruct To assemble or build again mentally; re-create.

Tabular Arranged or displayed systematically in table form.

Transcribe To write over again, or in the same words; to copy.

Translation A written communication in a second language having the same meaning as the written communication in a first language.

Synopsis

Reconstruction work for both steps and choreographies can include any of the following steps:

· Transcribing from facsimile form,

· Translating from a source language into English, and

· Creating a tabulated reconstruction of the dance.

A concordance of the work including all of these techniques can facilitate the understanding of the reconstruction process. But not all of these steps are required, nor are they always necessary. You can always start with someone else’s transcription, translation, or reconstruction. The following pages will define these techniques and demonstrate their use. Subsequent to these are example concordances of 15th Century Burgundian, 16th Century French, 16th Century Italian, and 16th Century English dances. A conclusion follows as well as a partially annotated bibliography.

Transcription

Generating a transcription of the facsimile is usually the first technique used in dance step or choreography reconstruction. By creating a transcription, your first focus is on correctly identifying each character of a word. This identification improves your familiarity with the language and the written text. This identification will also reduce translation or reconstruction errors.

Example Facsimiles

|

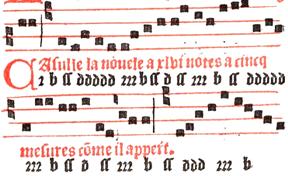

Cassulle la Nòuele from L’art et instruction de Bien Dancer, Paris c. 1490, by Toulouze.

|

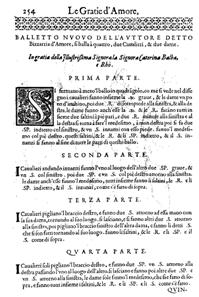

Bizzarria d’Amore from Le Gratie D’amore. 1602 by Cesare Negri

|

Start with an original complete printed copy of the facsimile of the dance on which you are working. Now, type the text of the facsimile, word-for-word. Try not to make alterations or corrections from the original type settings in the beginning. Mistakes in spelling, omitted letters, and lines that terminate with a syllable of a word, the remainder of which is carried to the next line, should be maintained. Note in your transcription that you have changed the original typeface to ‘Times New Roman’ or some other type face. Special symbols should be used to preserve the original type characters as described. Examples of some of these are in the table below. If you’re using Microsoft Word, these symbols are usually located under ‘insert/symbol.’ The table below is a partial list of special characters that may be used in direct transcription. Consult the bibliography for reference material to help understand these symbols in a period context.

Examples of Special Characters Used in Direct Transcription

Special Character Character Description

à Latin Small Letter ‘A’ with Grave

ã Latin Small Letter ‘A’ with Tilde

è Latin Small Letter ‘E’ with Grave

ẽ Latin Small Letter ‘E’ with Tilde

ò Latin Small Letter ‘O’ with Grave

ſ Latin Small Letter Long ‘S’

Example direct transcription

Nel

quinto tempo, ſi pigliara la Fè ſiniſtra, et ſi farà il

medeſimo

che s’è fatto di ſopra; ma la Dama farà le ſteſſe volte del

Contrapaſſo,

et l’ Huomo in cambio di eſſe farà due Seguiti fiancheggiati

indietro, et al=

tri due innanzi: poi finiranno gratioſamente il Ballo, pigliando l’ Huo=

lo la man’ ordinaria della Dama, et facendo inſieme la Riuerenza.

The direct transcription of your dance can now be modified to facilitate translation. Changes can include replacing omitted letters, correcting spelling errors, recombining split words, replacing special characters with modern characters, and removing abbreviations. Examples of these are in the following table below. Documentation of changes to the direct transcription resulting in the modified transcription could be marked in color or italics.

Examples of Corrections to Direct Transcription

|

Direct Transcription |

Modified Transcription |

Modification |

|

Italian |

||

|

che ſtandoſi le perſone |

che standosi le persone |

The Latin small letter long ‘S’ is replaced with the Latin small letter ‘S’ |

|

l’Hue= mo |

l’Huemo |

The hyphen ‘=’ is removed and the remainder of the word, which had been carried to the next line, is combined with the syllables that had been at the termination of the line. |

|

Ri= uerenza graue |

Riverenza grave |

The Latin small letter ‘U’ is replaced with the Latin small letter ‘V’. The hyphen ‘=’ is removed and the remainder of the word, which had been carried to the next line, is combined with the syllables that had been at the termination of the line. |

|

Trabuchet i |

Trabuchetti |

The Latin small letter ‘T’ is inserted to complete spelling. |

|

’ Huomo |

l’Huomo |

The Latin small letter ‘L’ is inserted to complete article. |

|

l’ Huomo |

l’Huomo |

The Space character is removed. |

|

Seguiti ordinarij |

Seguiti ordinarii |

The Latin small letter ‘J’ is replaced with the Latin small letter ‘I’. |

|

French |

||

|

vn double |

un double |

The Latin small letter ‘V’ is replaced with the Latin small letter ‘U’. |

|

Pieds ioinðs |

Pieds joincts |

The Latin small letter ‘I’ is replaced with the Latin small letter ‘J’. The special symbol ‘ð’ is replaced with the Latin small letters ‘C’ and ‘T.’ |

|

ddd |

double double double |

The abbreviations for double are removed. |

|

English |

||

|

iiij tymes |

four (iv) times |

The Latin small letter ‘J’ is replaced with the Latin small letter ‘I,’ then converted to the Roman Numeral ‘iv’ or written out as ‘four.’ |

|

That againe |

That again |

The Latin small letter ‘E’ is removed from ‘againe’ to create modern spelling. |

|

first Wo. |

first woman |

The abbreviation for woman is removed. |

|

the 2. as much |

the second as much |

The abbreviation for second is removed. |

|

Meete againe wth a d. |

Meet again with a double |

The Latin small letter ‘E’ is removed from ‘Meete’ and ‘againe’ to create modern spellings, the Latin small letter ‘I’ is inserted to complete ‘wth’, the abbreviation for double is removed. |

A side-by-side comparison of the direct transcription to the modified transcription of your dance can help others understand what changes you are making to the original dance. This kind of comparison is also the easiest way to directly compare the transcriptions. The original transcription is the left column; the modified transcription is the right column. An attempt should be made to keep phrasing consistent; sentences can be split at punctuation marks where possible.

They would appear as the following:

|

Left Column In the left column, no alterations or corrections have been made from the original type settings to the direct transcription. Mistakes in spelling, omitted letters, and or lines that terminate with a syllable of a word the remainder of which is carried to the next line are maintained. The original typeface has been changed to ‘Times New Roman,’ but special symbols have been inserted to preserve the original type characters. |

Right Column In the right column, the direct transcription has been modified to facilitate translation. Changes can include replacing omitted letters, correcting spelling errors, recombining split words, replacing special characters with modern characters, and removing abbreviations. Documentation of changes to the direct transcription resulting in the modified transcription could be marked in color or italics. |

Translation

If you do not have a working knowledge of the language in which your dance is written, the starting translation of your dance can be produced by processing the modified transcription through an online machine translator from the source language to the target language. This essentially translates each word as if it were the modern source language into modern English. Parts of speech, such as verb tense, are often translated poorly. This kind of translation contains many errors and inaccuracies.

Example online machine translation:

In the third time, the single Man will make the same one that harà made the Lady, & when arrivarà in head to knows it, dou’ she trovarà, lapigliarà for the man’ ordinary, & will make with two Puntate, one forward, & the other behind, with the Riverenza, like before.

The resulting translation should be corrected by hand. This includes correcting different parts of speech, changing definitions from modern meanings to more appropriate meanings contemporary to the dance, and translating words or phrases that were not recognized by the online machine translator. Technical step descriptions should be left in the dance’s contemporary language and can be demarked with color or italics. Examples of step names include Riverenza grave or Seguito ordinario. For translation aids consult the bibliography.

A side-by-side comparison of the modified transcription to the translation helps a reader understand the translation process. Someone looking over your translation can directly see certain word choices and grammar decisions. The modified transcription is the left column; the translation is the right column. An attempt should be made to keep phrasing consistent; sentences are split at punctuation marks where possible.

|

Left Column In the left column, the direct transcription has been modified to facilitate translation. Changes can include replacing omitted letters, correcting spelling errors, recombining split words, replacing special characters with modern characters, and removing abbreviations. Documentation of changes to the direct transcription resulting in the modified transcription could be demarked in color or italics. |

Right Column In the right column, the resulting machine translation has been corrected by hand. This includes corrected different parts of speech, changed definitions from modern meanings to more appropriate meanings contemporary to the dance, and translated words or phrases that were not recognized by the online machine translator. Technical step descriptions are left in the source language and are demarked in color or italics. Examples include Riverenza grave or Seguito ordinario. |

Reconstruction

The following points should be considered before reconstructing a dance.

- Identify the steps within the dance. List them and identify their timing.

- Identify placement and movement directions.

- Identify the timing and structure of the music. Music is possibly the most important indicator of how to perform the dance.

- Section the choreography according to verse/chorus structure or according to the playing of the music. Work individually with each of these sections, but let them influence the other sections.

- Use physical characters (chessmen, for example) to first test the concordance, and then test with live dancers. You may also prefer to draw diagrams on paper.

Example Reconstruction Notes

The following sequences form Burgundian Basse dances in which some combination of the ‘measure’ determines the number of doubles, singles, and reprises in a progression of the dance. Forming a chart of the style, such as below, makes reconstructing the dance that much more easily accomplished. The steps are described and notated in the following manner: pas simple (s), pas double (d), reprise (r), and branle (b). No description is given for the reverence (r).

Burgundian Basse Dance by Measure and Size

|

|

Size |

|||

|

petite (d) small |

moyenne (ddd) average |

grande (ddddd) large |

||

|

Measure |

mesure très parfaite ss {doubles} ss rrr b very perfect measure |

ss d ss rrr b |

ss ddd ss rrr b |

ss ddddd ss rrr b |

|

mesure plus que parfaite ss {doubles} ss r b more than perfect measure |

ss d ss r b |

ss ddd ss r b |

ss ddddd ss r b |

|

|

mesure imparfaite ss {doubles} rrr b imperfect measure |

ss d rrr b |

ss ddd rrr b |

ss ddddd rrr b |

|

Tabulation & Concordance

A tabulation or concordance of your dance communicates an understanding of how the choreography was reconstructed. Specifically, it allows the reader to examine how the facsimile was adapted and then how those words were translated into performable steps and movements. It is a simple and easily understandable way to combine timing, movements, and steps with the working translation and the modified source language transcription.

Some fields that can be used in the tabulation or concordance to describe the reconstruction are listed below. You should decide which fields to include, these are just suggestions.

Field Description

Repeat This field defines which repeat of the music is played for those steps listed in the following fields. The letter defines which section of the music is played; the superscript defines which playing of repetition of the section is performed. This field depends on how the music has been reconstructed. For example, this could appear as follows: A¹, A², B¹, B², C¹, C², D¹, and D² or A¹, B¹, C¹, A², B², and C².

Counts (Beats) This field defines how many counts (beats) are used for the steps listed in the following field (‘Step’). For example, a double in English Country dance equals four counts (beats).

Step This field defines which step is to be performed. For example, Seguiti ordinarii or double.

Starting Foot This field defines the starting foot, in order, for the steps listed in the proceeding field (‘Step’). This field is important where the dance description specifies with which foot a step is performed. For example two reprise could be ‘left, left’ or ‘left, right.’

Description This field describes the movements the dancers are making for the steps listed in the proceeding fields. For example, ‘walking to the head of the hall.’

Suggested calling This field suggests what words could be called while teaching the dance to help students remember which steps are in the dance. The field also suggests to other instructors how to teach the dance.

Translation This field is the resulting machine translation that has been corrected by hand. This includes corrected different parts of speech, changed definitions from modern connotations to more appropriate connotations contemporary to the dance, and translated words or phrases that were not recognized by the online machine translator. Technical step descriptions are left in the source language.

Transcription The direct transcription of the dance has been modified to facilitate translation. Changes can include replacing omitted letters, correcting spelling errors, recombining split words, replacing special characters with modern characters, and removing abbreviations. Documentation of changes to the direct transcription resulting in the modified transcription could be demarked in color or italics.

Example Concordances

The following concordances serve as illustrations of different facets of the reconstruction process. They differ in complexity and difficulty, but each has something valuable to study. Each is only a partial reconstruction of a dance.

15th Century Burgundian

This concordance is a good example of how period abbreviations can be turned into a performable dance. Once the basic construction of a Burgundian Basse dance is understood, practically any reconstruction is effortless. The concordance below displays the transcription and translation into step form. The number of counts (or beats) is possibly the most important field. Mastering the timing of this kind of dance is often the most difficult part for a dancer to learn. The following dance, Cassulle la Nòuele comes from L’art et instruction de Bien Dancer, Paris c. 1490, by Toulouze.

Casulle la Nòuele

|

Counts |

Step |

Translation |

Transcription |

||

|

3 |

reverance |

reverance |

|

r |

|

|

3 |

branle left |

branle |

b |

||

|

3 |

single left, single right |

single, single |

large imperfect measure |

ss |

grande mesure imparfaite |

|

15 |

double left, double right, double left, double right, double left |

double, double, double, double, double |

ddddd |

||

|

9 |

reprise right, reprise left, reprise right |

reprise, reprise, reprise |

rrr |

||

|

3 |

branle left |

branle |

b |

||

|

3 |

single left, single right |

single, single |

small very perfect measure |

ss |

petite mesure très parfaite |

|

3 |

double left |

double |

d |

||

|

3 |

single right, single left |

single, single |

ss |

||

|

9 |

reprise right, reprise left, reprise right |

reprise, reprise, reprise |

rrr |

||

|

3 |

branle left |

branle |

b |

||

|

3 |

single left, single right |

single, single |

large imperfect measure |

ss |

grande mesure imparfaite |

|

15 |

double left, double right, double left, double right, double left |

double, double, double, double, double |

ddddd |

||

|

9 |

reprise right, reprise left, reprise right |

reprise, reprise, reprise |

rrr |

||

|

3 |

branle left |

branle |

b |

||

|

3 |

single left, single right |

single, single |

small very perfect measure |

ss |

petite mesure très parfaite |

|

3 |

double left |

double |

d |

||

|

3 |

single right, single left |

single, single |

ss |

||

|

9 |

reprise right, reprise left, reprise right |

reprise, reprise, reprise |

rrr |

||

|

3 |

branle left |

branle |

b |

||

16th Century French

A good place for beginning reconstruction is with the 16th Century Branles found in Thoinot Arbeau’s Orchesographie, Langress,1589. This source is readily available in translation. It provides a number of dances with which to compare style and structure with step descriptions and music provided. This reconstruction is valuable because it points out the importance of music while studying the dance; the repeat of the first section is only apparent in the music.

Branle Charlotte

|

Counts |

Step |

Translation |

Transcription |

||

|

4 |

Double left. |

Left foot large. |

These four steps make a double left. |

Pied largy gaulche. |

Ces quatre pas fŏt vn double a gaulche. |

|

Right foot approach. |

Pied droið approché. |

||||

|

Left foot large. |

Pied largy gaulche. |

||||

|

Join feet. |

Pieds ioinðs. |

||||

|

1 |

Kick left. |

Left foot in the air. |

|

Pied en l’air gaulche. |

|

|

1 |

Kick right. |

Right foot in the air. |

Pied en l’air droið. |

||

|

4 |

Double right. |

Right foot large. |

These four steps make a double right. |

Pied largy droið. |

Ces quatre pas fŏt vn double a droið. |

|

Left foot appraoch. |

Pied gaulche approché. |

||||

|

Right foot large. |

Pied largy droið. |

||||

|

Join feet. |

Pieds ioinðs. |

||||

|

10 |

Repeat above. |

There is a repeat in the music. |

|||

|

4 |

Double left. |

Left foot large. |

These four steps make a double left. |

Pied largy gaulche. |

Ces quatre pas fŏt vn double a gaulche. |

|

Right foot approach. |

Pied droið approché. |

||||

|

Left foot large. |

Pied largy gaulche. |

||||

|

Join feet. |

Pieds ioinðs. |

||||

|

1 |

Kick left. |

Left foot in the air. |

|

Pied en l’air gaulche. |

|

|

1 |

Kick right. |

Right foot in the air. |

Pied en l’air droið. |

||

|

2 |

Single right. |

Right foot large. |

These two steps make a single right. |

Pied largy droið. |

Ces deux pas fŏt simple a droið. |

|

Left foot appraoch. |

Pied gaulche approché. |

||||

|

1 |

Kick left. |

Left foot in the air. |

|

Pied en l’air gaulche. |

|

|

1 |

Kick right. |

Right foot in the air. |

Pied en l’air droið. |

||

|

1 |

Kick left. |

Left foot in the air. |

Pied en l’air gaulche. |

||

|

2 |

Single left. |

Left foot large. |

These two steps make a single left. |

Pied largy gaulche. |

Ces deux pas fŏt simple a gaulche. |

|

Right foot approach. |

Pied droið approché. |

||||

|

1 |

Kick right. |

Right foot in the air. |

|

Pied en l’air droið. |

|

|

1 |

Kick left. |

Left foot in the air. |

Pied en l’air gaulche. |

||

|

1 |

Kick right. |

Right foot in the air. |

Pied en l’air droið. |

||

|

4 |

Double right. |

Right foot large. |

These four steps make a double right. |

Pied largy droið. |

Ces quatre pas fŏt vn double a droið. |

|

Left foot appraoch. |

Pied gaulche approché. |

||||

|

Right foot large. |

Pied largy droið. |

||||

|

Join feet. |

Pieds ioinðs. |

||||

16th Century Italian

Probably the most difficult to reconstruct are the dances of 16th century Italy. These dances require more translation and a working vocabulary of more advanced and specific dance steps. In the concordance below, a description field is included to show how the translation and transcription were interpreted into the movements described to the dancers. The following dance, Le Bellezze D’Olimpia, come from Fabrito Caroso’s Il Ballarino, Venice, 1581.

Le Bellezze D’Olimpia

|

Rep |

Cts |

Step |

Description |

Translation |

Transcription |

|

A¹ |

12 |

1 Riverenza grave |

Man ends by slightly turning to the left and facing partner. |

Making oneself together little to the encounter a Riverenza grave, |

Facendosi insieme un poco all’incontro la Riverenza grave, |

|

A² |

12 |

2 Continenze |

and two Continenze, one to the left, and the other to the right: |

et due Continenze, l’una alla sinistra, et l’altra alla destra: |

|

|

B¹ |

12 |

2 Seguiti ordinarii |

Trade places: man passes behind while woman passes in front, end by dropping hands. |

behind the Man, holding the hand with a half Moon, will make to pass the Lady with two Seguiti ordinarii making of again it in the same time another two behind: the end of the same, changing places, placing the Man to the left, and the Lady to the right then letting go of the hand, |

dopò l’Huomo, tenendo la mano à modo di meza Luna, farà passare la Dama con due Seguiti ordinarij, facendone anch’esso nel medesimo tempo altri due indietro: al fine de’ quail, cambiaranno luogo, ponendosi l‘Huomo alla sinistra, et la Dama alla destra poi lasciandosi la mano, |

|

B² |

12 |

2 Seguiti ordinarii |

Circle over left shoulder, end facing partner slightly apart. |

another turn with two Seguiti to the left, separated somewhat: |

si voltaranno con due altri Seguiti alla sinistra, discostandosi alquanto: |

|

C¹ |

6 |

2 Seguiti spezzati |

Man flanking forward, first to the right then the left as woman retreats. End clasping hands, woman’s left in man’s right. |

last and all of they, finding again itself to the encounter, the Man will make two Seguiti spezzati flanking forward, and three Trabuchetti, beginning with the left foot: and the same movement will make the Woman behind. |

et all ultimo di essi, ritrovandosi all’incontro, l’Huomo farà due Seguiti spezzati fiancheggiati innanzi, et tre Trabuchetti, principiandosi col piè sinistro: et gl’istessi farà la Dama indietro. |

|

6 |

3 Trabuchetti |

16th Century English

The Inns of Court manuscripts, which end post period, are one of the main primary sources for Almans; they contain a number of dances, each with different authors but similar tablature. Almans are fairly easy to reconstruct from the primary sources as the Inns of Court manuscripts are in English. These sources allow a person to reconstruct a dance from multiple sources, rather than just one dance. The concordance below demonstrates this value by comparing five different sources to form a single reconstruction.

The Black Alman

|

Cts |

Step |

Translation |

Transcription |

||||

|

Rawl. Poet. 108 |

SRO DD/WO 55/7 |

Harleian 367 |

Douce 280 |

Inner Temple vol 27 |

|||

|

|

The Black Allman |

The new cycillia allemaine |

The blacke Almaine |

the blacke allman |

.Blacke. |

8 Measure The Black Almaine |

|

|

Honor. |

Honour. |

|

|||||

|

16 |

4 doubles forward. |

four doubles forward. |

a duble forward hoppe iiij tymes // |

ffower doubles forwarde, |

fouer double forward then |

Fowre doubles forward, |

Syde 4 double round about the Hall | and |

|

close the last double to face, |

close the last double face to | face, |

||||||

|

part hands, |

parte handes, |

part handes with |

Then part your hands and |

||||

|

4 |

1 double back left, away from partner. |

a double back from one another |

ij singles | backe |

a double backe one from an other, |

a double backe face to face & |

a .d. backe, | |

Goe all | in a double back one from another and | |

|

4 |

1 double forward right, toward partner, end turning to left. |

a double forward |

ij syngles forward [ij]// |

a double | meetinge againe, |

a double | forward |

meete againe with a .d., |

meet a double againe, Then |

|

4 |

1 double forward left, away from partner, end tuning to face partner. |

then a double to the left hand and |

a duble forward | |

a double on your lefte hand & |

then a double to the left hand & |

A .d. on your lefte hand, |

goe a | double to the left hand and |

Conclusion

Through reconstruction you have the ability to contribute to your local dance practice as well as the Society as a whole. Examining dance steps and choreographies already common to the Society can help correct common errors and preconceived notions of a dance as well as offer new variations. As a dance or style becomes more common, it is possible to allow ourselves to pick up inconsistent habits. In our familiarity, we begin to detach ourselves from what was described in period. New and fresh eyes can help maintain style and technique.

However, you also serve the dance community by reconstructing unfamiliar dances. New choreographies help keep the community excited and willing to learn. They stop the dance repertoire from becoming stagnant and encourage growth. This kind of reconstruction work challenges every dancer because it adds to our wealth of knowledge. Placed in the context of familiar dances, these works can help generate new theories about the form and manner of different dance styles.

Both of these endeavors, the examination of dance steps and choreographies already common to the Society and the reconstruction of unfamiliar dances, are essential to the success of the dance community within the Society. Keeping in mind the reconstruction techniques described above, it is important to ask yourself questions that affect your reconstruction process before beginning any dance. This can save you time and hopefully some frustrations. When choosing to undertake one of these measures, consider the following before starting the reconstruction process:

How much work do you want to do?

If you have limited time or are less experienced, then I would suggest beginning with a 16th Century English alman from the Inns of Court manuscripts. They are in English and relatively simple with multiple sources. Also, they have all been reconstructed, so you have something to compare your work against.

If you are ready to devote significant time and feel prepared, then transcribe and translate a dance and its steps from the 16th Century Italian manuscript Il Ballarino by Fabrito Caroso. There is not a current translation of this work and many of the dances are not reconstructed. The figures and timing of these dances are complex and require significant time to decipher.

Are you working with a dance you already know?

Reconstructing a dance you have already learned introduces to you how other people have made decisions on timing and placement. It also gives you the support of a finished product to compare your work too. Sometimes, step and dance figures can be tricky or confusing in their descriptions. By looking at a familiar dance, you give yourself a chance to make new decisions. Be careful, though. You should be aware that your thought process is already prejudiced by another reconstructor’s decisions.

Have you reconstructed more than one dance within the same style?

Working with a style you already know is especially useful when reconstructing a dance. If you know multiple dances of the same style, then you can see trends in the choreography. You may identify common figures and patterns that will be used as tools for your reconstruction process. If you have need to question a section in a dance you are reconstructing, you can rely on your knowledge of other dances of the same style to help solve the problem.

Are you reconstructing from one source, or from a combination of sources?

Both reconstructions from one source and multiple sources have merit. Often times you only have one source for step or dance descriptions. You can make your reconstruction as close a reproduction as possible without having to consider conflicting or confusing information. But when you have multiple sources, you can then make choices against an array of information.

Are you working from your own reconstruction of the music, or someone else’s reconstruction?

Music is sometimes the most important key to understanding a difficult figure or sequence. If you are limited to an existing recording of the music or someone else’s reconstruction in sheet music form, this reliance hampers your ability to correctly reconstruct a dance. Often, a musician will recreate the music as they believe will be most pleasing to the ear and disregards whether it will be a danceable piece. Example problems could be the tempo being to slow or to fast, the repeat structure being wrong, or the number of times through iterations of the music not being the same as the number needed for the dance. The best way to combat this conflict between choreography and music is to educate yourself about music and make contacts within the music community.

Are you reconstructing a new dance, or are you checking a current reconstruction?

You should probably understand why you are reconstructing a dance before even beginning. Identify your goal for that dance. It can be a very difficult process and sometimes frustrating to reconstruct a dance that no one knows. Also, there is hardly anyone who can help you if you have questions. Reconstructing new dances requires you to be more self sufficient. And, if you ask for help, it requires more work from those you ask because they too do not know the dance.

If you are checking a current reconstruction, then you need to remember that already knowing the dance will affect your decisions. You may do this type of reconstruction to learn the reconstruction habits and techniques of an experienced reconstructor. Or, you may have been asked to proofread a reconstruction for errors and so are reconstructing the dance yourself for comparison.

The above questions are by no means a comprehensive list. As you gain more experience, you will begin to understand your own work methods and will start to develop your own techniques. It is important to realize that any reconstruction effort you make is useful – regardless of your experience or skill. By starting to examine primary source material, you will learn to appreciate how existing dance steps and choreographies are transformed into performable dances. You also improve your sense of style and technique as a dancer and your methods of instruction as a teacher. Every attempt you make at reconstruction is worthy.

Bibliography

Reconstruction Aids

Renaissance Dance Manuals

Arbeau, Thoinot. Orchesography. Langress,1589.

This 16th century French manual is essential to a starting reconstructor. It contains a wide variety of dances, including bransles, almans, and galliards which are already commonly performed and have music widely available. The descriptions for these dances and their steps are generally more readable and more easily understood than the other manuals. It contains style elements common to the other manuals, so it is a good place to start before tackling the more complicated steps, patterns, and descriptions. This is also a good source because there is a reliable translation readily available.

Caroso, Fabritio. Nobiltà di dame. Venice, 1600.

This 16th century Italian manual is good to study if you are working on 16th century Italian dance. This manual is the second edition of Il Ballarino, and a good source of comparison for that manual. It contains fewer dances, but more step descriptions and etiquette rules. This is also a good source because there is a reliable translation readily available. However, these dances and their steps are more complicated and can result in multiple interpretations. Also, this style of dance is less common in the Society. Musical recordings for this material are rarer and you need to be aware that the specific music may not be written to correspond to the dance.

Caroso, Fabritio. Il Ballarino. Venice, 1581.

This 16th century Italian manual is the first to study if you are working on 16th century Italian dance and are willing to take a challenge because there is no current translation available. It is the original source for Noblita di Dame and possibly Negri’s Le Gratie D’amore and can, therefore, serve to answer many reconstruction questions from these two manuals. However, these dances and their steps are more complicated and can result in multiple interpretations. Also, this style of dance is less common in the Society. Musical recordings for this material are rarer and you need to be aware that the specific music may not be written to correspond to the dance.

Negri, Cesare. Le Gratie D’amore. 1602.

This 17th century Italian manual is good to study if you are working on 16th century Italian dance. This manual steals from Il Ballarino and Noblita di Dame, and is a good source of comparison for that manual. It contains many of the same dances, but descriptions are often different. This is also a good source because there is a reliable translation available. However, these dances and their steps are more complicated and can result in multiple interpretations. Also, this style of dance is less common in the Society. Musical recordings for this material are rarer and you need to be aware that the specific music may not be written to correspond to the dance.

Playford, John. The English Dancing Master: Or Plaine and Easy Rules for the Dancing of Country Dances, with a tune to Each Dance. London, 1651.

This 17th century English manual is good to study if you are working on 17th century English country dance. This style of dance is very common in the Society and many dances are already reconstructed for comparison. Music for these dances is also abundant. Though the manual itself is out-of-period, examining these dances can form many good habits and techniques for reconstructing dance. This manual is also a good source because it is readily available and was originally written in English. However, some of the dances are more complicated than they appear and can result in multiple interpretations.

Toulouze. L’art et instruction de Bien Dancer. Paris, c. 1490.

This 15th century Burgundian manual is good to study if you are working on Burgundian basse dances. This style of dance is not common in the Society, but one dance in particular is widely performed. Once the style is learned, then the other dances are quickly understood. Be aware that the step timing is tricky in the beginning and is usually what stops people from learning this style. These dances are also good because they do not require set music and can be improvised. This is also a good source because it is readily available.

Contemporary Dance Resources

Clossen, Ernest. Materials for the Study of the Fifteenth-century Basse Dance, Brooklyn, NY: The Institute of Medieval Music, 1968.

This work is valuable because it makes Burgundian dance accessible to those who only speak English. This work includes a facsimile with introduction and a transcription by Clossen. He discusses steps and style. However, more recent scholarship has identified faults and inaccuracies on the part of Clossen’s research so this book is handier for its facsimile and transcription.

Evans, Mary Stewart. Orchesography. Kamin Dance Pub., 1948. Reprint of Orchesographie, 1589.

This work is very valuable because it makes French dance accessible to those who only speak English and it offers both a facsimile of some of the book and translation of all of it. However, the work does contain flaws, so it is useful to examine the original French along side it.

Kendall, Gustavia Yvonne. Le Gratie D’amore 1602 By Cesare Negri: Translation and Commentary. University Microfilms International, dissertation (Stanford University), 1985. Reprint of Le Gratie D’amore, 1602.

This work is valuable because it makes Italian dance accessible to those who only speak English. It is further useful because it contains a facsimile of the original with the translation. It is important to be aware that this translation does contain flaws and is, therefore, is not completely consistent.

Smith, William A. Fifteenth-Century Dance and Music: The Complete Trnscribed Tretises and Collections in the Domenico Piacenza Tradition. Volumes 1 and 2. Pendragon Press. Hilsdale, NY, 1996.

This work is essential to the study of 15th century Italian dance. It is a nearly complete translation with transcription of all the 15th century dance manuscripts known to exist at the time of publication. The first volume includes music and full translation of the largest and most comprehensive manuscripts. The second volume contains comparative tabulations of the dances across the twelve manuscripts.

Sutton, Julia. Courtly Dance of the Renaissance: A New Translation and Edition of the “Noblità di Dame” (1600): Fabrito Caroso. Translated and Edited by Julia Sutton. Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1995.

This work is valuable because it makes Italian dance accessible to those who only speak English. It is further useful because it contains a facsimile of the original with the translation. This is the mostly widely used text in the Society after John Playford’s The English Dancing Master and Sutton’s translation of Mary Stewart Evan’s translation of Orchesography. It is the best introduction to 16th century Italian dance and style and has comprehensive discussions on most aspects of this type of dance. What it lacks is a facsimile or a transcription of the original.

Translation Aids

These resources are included here as further contemporary reference to grammars and language resulting in more period translations. My purpose for including these is not to teach you how to translate, but rather to help you realize translation opportunities.

Online Modern Translations

Online Modern Dictionaries

Online Renaissance Dictionaries

Cotgrave, Randle Compiler. A Dictionary of the French and English Toungues. London, 1611. Printed by Adam Islip. http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/cotgrave/.

Florio, John. Queen Anna's New World of Words followed by Necessary Rules And Short Observations For The True Pronouncing And Speedie Learning Of The Italian Tongue, 1611. An Italian/English Dictionary. http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/florio.

Contemporary References

The following list is partially adapted from the Appendix (Simonini , 110-112) of R. C. Simonini’s Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England. Simonini’s Appendix served as “a checklist of grammars, language manuals, and dictionaries for the study of Italian published in England during the Renaissance (Simonini , 110).”

Florio, John. Florio His firste Fruites: which yeelde familiar speech, merie Proverbes, wittie Sentences, and golden sayings. Also a perfect Induction to the Italian, and English tongues, as in the Table appeareth. The like heretofore, never by any man published. London: Thomas Dawson for Thomas Woodcocke, 1578. 4to.

Florio, John. Florios Second Frutes, To be gathered of twelve Trees, of divers but delightsome tastes to the tongues of Italians and Englishmen. To which is annexed his Gardine of Recreation yielding six thousand Italian Proverbs. London: Thomas Woodcock, 1591. 4to.

Florio, John. A Worlde of Wordes, Or Most copious, and exact Dictionarie in Italian and English, collected by Iohn Florio. London: Arnold Hatfielf for Edward Blount, 1598. folio.

Granthan, Henry. An Italian Grammar. 1575. Selected and Edited by R.C. Alston for English Linguistics, 1500-1800 (A Collection of Facsimile Reprints) No. 69. The Scholar Press Limited. Menston, England, 1968.

Granthan, Henry. La Grammatica Di M. Scipio Lentulo Napolitano da lui in latina lingua Scritta, & hora nella Italiana, & Inglese tradotta da H. G. An Italian Grammar Written in Latin By Scipio Lentulo a Neapolitane: And turned into Englishe by Henry Granthan. London: Thomas Vautrollier, 1587. 8vo.

Holiband. Campo Di Fior or else The Flourie Field of Foure Languages of M. Claudius Desainliens, alias Holiband: For the furtherance of the learners of the Latine, French, English, but chieflie of the Italian tongue. London: Thomas Vautroullier, 1583. 16mo.

Hollyband, Claudius. The Italian Schoole-maister: Contayning Rules for the perfect pronouncing of th’ Italian tongue: With familiar speeches: And certaine phrases taken out of the best Italian Authors. And a fine Tuyscan historie called Arnalt & Lucenda. Set forth by Claudius Holliband. London: Thomas Purfoot, 1583. 16mo.

Hollyband, Claudius. The Italian School-maister: Contayning Rules for the perfect pronouncing of th’ Italian tongue: With familiar speeches: And certain Phrases taken of the best Italian Authors. With a historie called Arnalt and Lucenda. Set forth by Clau: Hollyband, Gent: And now revised and corrected by F.P. an Italian, professor and teacher of the Italian tongue. London: Thomas Purfoot, 1608. 8vo.

Hollyband, Claudius. The Pretie and Wittie History of Arnalt and Lucenda: with certain rules and dialogues set foorth for the learner of th’ Italian tong: and dedicated unto the worshipfull, Sir Hierom Bowes, Knight. By Claudius Hollyband, scholemaster, teaching in Paules Churchyard by the signe of the Lucrece. London: Thomas Purfoote, 1575. 16mo.

London, H. G. An Italian Grammar Written In Latin By Scipio Lentulo A Neapolitane: And turned in Englishe: By H. G. London: Thomas Vautroullier, 1575. 8vo.

Sanford, Joaness. A Grammar, or Introduction to the Italian Tongue. By Joaness Sanford. Oxford: J. Barnes, sold by S. Waterson, 1605. 4to.

Sanford, John. A Grammar or Introduction to the Italian Tongue. 1605. Selected and Edited by R.C. Alston for English Linguistics, 1500-1800 (A Collection of Facsimile Reprints) No. 324. The Scholar Press Limited. Menston, England, 1972.

Sferrazzo, Antonio. Verbi Italiani Irregolari e Difettivi: Coniugati per Esteso. Casa Editrice Ceschina, Milano, 1961.

Thomas, William. Principle Rules of the Italian Grammar. 1550. Selected and Edited by R.C. Alston for English Linguistics, 1500-1800 (A Collection of Facsimile Reprints) No. 78. The Scholar Press Limited. Menston, England, 1968.

Modern References

The usefulness of these sources will depend on your familiarity with a language. For example, if you know the grammar of a language, you may need to only keep a dictionary as reference during your study and reconstruction. Theses sources are examples of Italian references. Consider learning about the language today, but also studying the language as it was used contemporary to the dance manual you are examining.

Cinque, Guglielmo. Italian Syntax and Universal Grammar. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995.

Colaneri, John and Vincent Luciani. 501 Italian Verbs. Barons Educational Series, Inc., New York, 1992.

McIntosh, Colin. The Oxford Started Italian Dictionary. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999.

Simonini, R.C. Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England. The University of Carolina Studies in Comparative Literature, Chapel Hill, 1952.

Master Philip White

Craig W. Shupeé

Province of Tree-Girt-Sea, Midrealm

philipwhite@hotmail.com