|

|

Proceedings of the Known World Dance Symposium 2007 |

Survey of European Dance Sources

1400 - 1700

Peter and Janelle Durham

(Trahaearn ap Ieuan and Jane Lynn of Fenmere)

Burgundian Basses Danses

There daunseth to gether a man and a woman, holding eche other by the hande or the arme… the meving of the man wolde be more vehement, of the woman more delicate, and with lasse advauncing of the body, signifienge the courage and strenthe that ought to be in a man, and the pleasant sobreness that shulde be in a woman.

-The Boke Named the Governour, 1531

About the Sources

There is a broad array of information surviving on the repertoire of dances commonly known as Burgundian basse dances. Interestingly, the majority of the period sources appear to be derived from an original text which has been lost. The Brussels manuscript may be copied directly from the prototype, the Toulouze may be a direct copy, but researchers suspect there is one generation between it and the original. Moderne is based on Toulouze, and the Coplande translation is from either Brussels or the original. It is possible to make observations about the evolution of basse dance by examining the details of these “generations” of text, and several modern researchers have attempted to do just that.

The manuscripts typically begin with a treatise (virtually identical throughout most sources) which discusses the theory and performance of basse dances. This is followed by a number of dances, which were tabulated as a tenor line, with abbreviations for the steps running on the line below the music, detailing the choreography.

Music

Music for these dances survives only in tenor lines, written in undifferentiated rhythmic values. Musicians were expected to improvise counter-tenor lines above the tenor. In outdoor settings, a sackbut might have played tenor notes while two shawms improvised counter melodies; a drum may have provided percussion. At intimate gatherings, ensembles might have included instruments such as flute, lute, viol, recorder or rebec. Or a solo wind player might have improvised a line of notes which refer back to the tenor.

Specific choreographies are often associated with multiple tenor lines, and it has been theorized that any set of steps can be danced to any basse music of the right length. In the Brussels and Toulouze manuscripts, dances are composed of 28-59 steps; in later sources, they are 14-29 steps (common basse having 20) plus a standardized 12 step retour or moitié.

Steps

Almost the entire basse dance repertoire is based on combinations of only 4 steps. Each step takes the same amount of time, referred to as a breve, believed to have a duration of 3-4 seconds.

Singles (ss). “the first step is done with the left foot raising the body and making the single step forward, and the second step is done with the right foot and one must raise the body and step a little forward.” Singles were always done in pairs; the pair evenly dividing the three beats of the breve. Thus, a pair of singles counts as one “step”.

Doubles (d). “The first double step is done with the left foot; one must raise one’s body and go three steps forward lightly, the first with the left foot, the second with the right foot, and the third with the left.” There were almost always an odd number (1, 3, or 5). The first double began on the left, the second on the right, and so on.

Desmarche (r). “The second desmarche must be made with the left foot, lifting the body and turning it a little towards the lady; and following, bringing the right foot near the left foot raising the body similarly.” Desmarches were done one at a time, or in clusters of three, always beginning on the right foot. In later sources, a desmarche was called a reprise.

Branle (b). “The branle must start with the left foot and end with the right foot, and is called a branle because one makes it swaying with one foot towards the other.”

|

Colophon from Toulouze, 1488 |

A courtly couple dance. Note musicians with flute and drum, the footwear and masks on the male dancers, and the inattentive spectators. |

Burgundy and France 1445-1500

· 1467. Philippe le Bon dies after a 48-year reign in which Burgundy has become the richest state in Europe. Charles the Bold becomes Duke of Burgundy, begins 10 year war with France. In 1482, Burgundy is absorbed into France.

· 1482. Marriage of Marie of Burgundy, daughter of Charles the Bold, to Maximillian of Austria.

Social Context

Basse dance is believed to have been an extremely graceful dance, with the tempo adjusted so steps could be light and unhurried. The treatise on basse emphasizes that one “walks peacefully, without great exertion, and as gracefully as possible.” Basse implies a dance that is low to the ground, and these choreographies do not include any hops or jumps.

As evidenced by the origin and ownership of various texts, Burgundian basses appear to have been known in France, England, Spain, and Italy.

Purpose of the manuscripts: “[The texts were] not intended to be read by performing musicians - dance musicians of the late fifteenth century surely played from memory… Rather, this volume was designed as an aid to a noble student of the basse danse, who needed to commit to memory a repertory of complex choreographies.”

Sample Dance: Alenchon

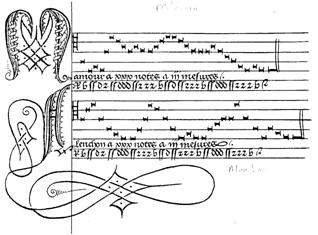

The top illustration shows a page from the Brussels manuscript; the lower dance is Alenchon. The lower illustration shows Toulouze’s version of the same dance.

In the Brussels example, the steps of the dance are notated as “R b ss d r ss d d d ss r r r b ss d ss r r r b ss d d d ss r r r b c.”

These steps were arranged into choreographies based on a structure of mesures. “There is a general rule in basse dances that one always makes a desmarche first of all then one must do a branle, and next, two single steps, then the double steps [1, 3, or 5], and then two single steps if the measure of the basse dance requires it, and then the desmarches [1 or 3], and then the branle.” Each specific arrangement had a term to describe it. The number of doubles determined whether it was petite, moierne or grande. It was called imperfect, perfect, or tres parfaites depending on whether the second set of singles was included.

|

|

|

Primary Sources

Paris, Biblio. nationale, f. fr. 5699. c. 1445. (Nancy ms.)

Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique, MS 9085. Approx. 1470. (Brussels manuscript.) Transcription and translation by Kronenfeld and Gill in Letter of Dance 14, July ‘92. Facsimile at Library of Congress. Linked from www.rendance.org/primary.html

S’ensuit l’art et instruction de bien dancer. (Toulouze) Published in Paris, c. 1496 by Michel Toulouze. Facsimile: www.pbm.com/~lindahl/toulouze/

Cervera, Archivo Histórico, Ms. c. 1496. Facsimile: www.pbm.com/~lindahl/cervera/

Antonius Arena, Ad suos compagnones, 1519. Facs: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k71525c

Coplande. “Maner of dauncynge of bace daunces.” Bodleian Library, Douce B. 507. 1521. Brussels translated into English.

Moderne. S’ensuyvent plusieurs basse dances, tant communes que incommunes. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Coll. Rothschild, vi bis-66, No. 19. c. 1529-1538. Facsimile: Editions Minkoff 1985. Facsimile: www.pbm.com/~lindahl/moderne/ (also a link to translation there)

Salisbury, 1497. Transcription: http://caagt.rug.ac.be/~vfack/ihdp/salisbur.html

Arbeau, 1589. Describes basse dance, says it is out of date.

Secondary Sources

Crane, Frederick. Materials for the Study of the Fifteenth Century Basse Dance. (Institute of Medieval Music, 1968.)

Heartz, Daniel. “The Basse Dance: Its Evolution circa 1450 to 1550.” Annales Musicologiques 6, 1958-63.

Jackman, James L. Fifteenth Century Basse Dances. Books for Libraries, 1980. Transcriptions of Brussels and Toulouze with dance descriptions from each source collated for easy comparison.

Kronenfeld, Nathan. “A Reconstruction of the Brussels Manuscript.” Letter of Dance 16, June 1993.

Recordings

15th c dances from Burgundy and Italy. Guildhall Waits. From www.dancebooks.co.uk. 4 dances

Music from the time of Richard III. York Waits, 1987. From amazon.com 3 dances

Sonare e Ballare. Bedford Waits. DHDS, 1990. 5 dances.

The Tape of Dance, Volume 2. Dani Zweig and Monica Cellio, LOD2, 1995. Includes 9 basses arranged by Mustapha al-Muhaddith; synthesizer by Delbert von Strassburg.

Domenico and Students

I will now present those balli and bassedanze which are

beyond the mundane, made for elegant halls, and only to be danced by very

proper ladies— not by those of the lower classes.

-Cornazano

About the Sources

Italian bassedanze and balli of the 15th century appear in the works of three Italian dancemasters.

Domenico da Piacenza (1390-1464) is credited as the first dance choreographer to establish an Italian school of the dance, and his students Cornazano and Guglielmo describe themselves as his “devoted disciples and fervent imitators”. De arte saltandi et choreas ducendi, from 1455, was written by anonymous scribes or students of Domenico. It includes 23 dances and their music as well as a theoretical treatise.

Antonio Cornazano (1430-1484) was an Italian poet and courtier, who presented his Libro dell’arte del danzare to the daughter of the Duke of Milan in 1455. A copy from 1465 survives. It contains a treatise and 11 of Domenico’s dances.

Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro / Giovanni Ambrosio (1420-1481) was a dance master, choreographer, composer, and theorist. His De practica seu arte tripudii survives in seven known versions, plus three existing fragments, dating from at least 1463 to 1510. It includes a theoretical introduction on the elements of dance and other topics. This is followed by the practice, which includes choreographies of approximately 31 dances: 14 bassedanze, and 17 balli.

Music

The sources describe 4 kinds of misura or measures.

· Bassadanza. a slow measure in 6.

· Quadernaria. A slow measure in 4.

· Saltarello. A fast measure in 2, similar to modern 3/2 or 6/4.

· Piva. The fastest measure, similar to our 6/4.

The bassedanze is a general term for four different kinds of dance, differing in tempo and steps. A bassedanze is danced to only one of these misura in any given dance. A ballo typically includes sections composed in a number of different measures.

Contemporary sources indicate that appropriate instrumentation would be either two or three shawms and a slide trumpet for dance festivals, or the harp, lute, and flute for quieter settings. The one-handed pipe and tabor are not seen in pictures, but are mentioned in literary documents.

Style

Guglielmo says the following 6 elements must be “minutely and perfectly grasped, for if one of these is lacking in any way, the art [of the dance] would not be truly perfect.”

· Misura. Measure is the ability to keep time to the music, so “steps will be in perfect accord with the aforesaid tempo.”

· Memoria. “It is necessary... to have a perfect memory... to recall all those elements that need to be remembered” while adapting to unexpected changes in the music.

· Partire di Terreno. In narrow rooms, “it is advisable to use one’s wits to measure and partition the ground...”

· Aiere. “An act of airy presence and a rising movement...” Domenico uses the metaphor of a gondola riding calm water, the waves “rising slowly and lowering themselves quickly.”

· Mayniera. Manner is an adornment or shading of the movement of the body to match the movement of the feet.

· Movimento corporeo. Dance must be “measured, mindful, airy, well-partitioned, and gracious... far easier to the shapely, the nimble, and those well-endowed with grace...”

|

|

Painted miniature from Guglielmo’s 1463 treatise. Shows appropriate clothing and musical accompaniment. The unusual handhold is a subject of academic debate: it is unknown whether hands were joined in this manner for dancing, or merely for the sake of the artist’s caprice. |

Northern Italy 1455-1465

· 1450-1476. Sforzas rule Milan, making their court a rival to the Medici’s, attracting scholars and exiles.

· 1464. Florence’s Cosimo de Medici dies at 75 while listening to one of Plato’s dialogues. Lorenzo heads Florentine state from 1469-92.

· Donatello’s art and Alberti’s architecture symbolize era.

Social Context

Period descriptions of a festival in Florence in April of 1459 reveal several things about the place of dancing in 15th century Italian society. This festival was held outdoors in the Mercato nuovo, where raised platforms were set for the musicians, and for those who “did not dance because of age or weight.” This festival was attended by “sixty youths dressed up for the beautiful dance, [forty of whom] wore clothing decorated with brocade” and by “nearly 150 ladies all coiffured and very ornately dressed.”

After a fanfare of twenty trombetti had announced the arrival of “important rulers and great champions,” “the pifferi and trombone players began to play a saltarello artistically and artfully constructed. Then every squire… chose his wife or a maiden and began dancing... they danced a great bit to the saltarello, then to various dances as requested by this person or that… they performed Lauro… Lioncello… Belriguardo”

“Two young women who were blessed with beautiful faces... went over to invite the gentle count… [he] took his place between them and danced without making a mistake…. men and women stood and bowed every time the three dancers passed by.... [then] they escorted him back to his place.”

In addition to social dancing, there is also a mention of a dance competition in Guglielmo’s autobiography: “A very great festival was held and I was pressured to dance. Prizes were given to me and to the woman who danced with me... a beautiful handkerchief of silk... and a purse.”

Theatrical dances, moresche, appear in contemporary sources: One in 1474 was “a morality in praise of Chastity (but with Cleopatra leading various ‘lascivious women of antiquity’) culminated in a bassadanza performed around Chastity by six ‘queens’, followed by 12 ‘nymphs’ who danced in a ring around them.” These were danced by dance-masters, by professional dancers, or by courtiers themselves.

Sample Dance: Mercantia

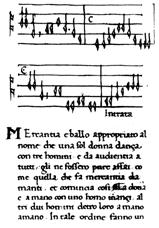

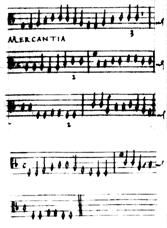

The dance Mercantia appears in Domenico, Cornazano, and most of the Ebreo manuscripts. Cornazanno says “Mercantia is a dance appropriate to the name, because one lone woman dances with three men and gives attention to all of them, as if she were a merchant of lovers.”

First do eleven tempi all four together, & the woman goes with one man, & the other two together: the woman should be with the couple in front & they stop. Next the men at the back should separate with six riprese sideways, the one going to the left hand and the other to the right. Next the woman does a half turn to the left hand. The man her parner goes forward with three doppii starting on the left foot, and the woman comes to remain with the other two men in a triangle. And next the man that is to the right departs with two sempii and one doppio starting on the left foot, & comes to touch the hand of the woman, and then turns to the right hand with two sempii & a doppio, starting on the right, and returns to his place, where he was. Next his partner that is to the left hand does the same. And note that the woman should do a volta tonda to turn, when the first man comes to touch her hand. And she should do this same to the second man. Next the top man should do a half turn to the right side. & then the menat the bottom take hands and do two singles & a double with the right foot in front, & change their places. Next that man which is at the top departs with two tempi of saltarello beginning with the left and finishing on the right. And he goes next to the woman. And then the woman turns toward the man, and the man touches her hand with a reverence on the left. And next the same man goes to the left hand of the woman. & he comes to take the man that is on the right hand with two singles and a double beginning on the right. And he who was on the left hand comes to take the woman with these same steps, and he remains with the woman.

|

|

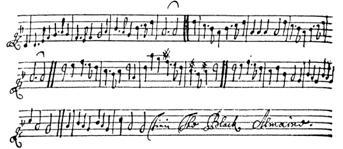

Left is part of the music and text for Mercantia from Cornazano. Right is the music, from the Guglielmo Ebreo ms. in Paris. The translation by Trahaearn is based on text from this latter source. |

|

Primary Sources

Domenico. Facimile: www.pbm.com/~lindahl/pnd/

Smith, A. William. Fifteenth Century Dance and Music: Twelve Transcribed Italian Treatises and Collections in the Tradition of Domenico da Piacenza. Pendragon Press, 1995. Includes introductory information, transcriptions and translations of multiple manuscripts, concordances, etc.

Sparti, Barbara. De practica seu arte tripudii. On the Practice or Art of Dancing. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993. Introduction, transcription, and translation of 1463 Guglielmo.

Sources

Kinkeldey, Otto. A Jewish Dancing Master of the Renaissance. Dance Horizons, 1966, reprint from 1929.

Stephens & Cellio. Joy and Jealousy: A Manual of 15th century Italian Balli. Self-published, 1997. Download at: http://sca.uwaterloo.ca/~praetzel/Joy_Jealousy/ Manual, including step reconstructions, dance reconstructions, and musical arrangements.

Wilson, D.R. The Steps Used in Court Dancing in 15th century Italy. Self-published, 1998.

Recordings

Mesura et Arte del Danzare. Balli Italiani del Quattrocento. Academia Viscontea I Muicanti. Ducale CDL 002, 1991. Available from iTunes.

Forse Che Si Forse Che No. Ferrarra Ensemble. Fonti musicali fmd 182, 1989. Out of print

To celebrate a prince. Alta. Dolmetsch Historical Dance Society, 1992. www.dhds.org.uk

See also: all recordings under Burgundian Basse section.

John Banys’s Notebook

About the Source

“It is a slightly embarrassing story,” wrote David Fallows in his introduction to the first transcription of the dances from John Banys’ notebook. In 1984 a colleague sent him copies of 13 dance melodies from a notebook found in the Derbyshire Record Office, but believing it to be Elizabethan, he filed and forgot them. In 1995, when passing them on to another colleague, he realized the music was much earlier, from about 1500. Two days later, he visited the office, and discovered that the notebook also contained 26 detailed choreographies, and a list of 91 dance titles. He realized the historical significance of the find, and quickly published the contents.

Fallows described the source as a “tiny pocket book, 12½ x 9 cm (4¼ x 3¾ inches). The volume consists of an outer cover plus three gatherings of, respectively, 11, 6, and 6 bifolia. Most leaves are of paper (now covered by transparent repairing paper and strengthened by Japanese tissue, making it almost impossible to see any watermarks); but parchment is used for the cover as well as for the outer and inner bifolia of each gathering plus the sixth bifolium of the first 11-bifolium gathering.”

In addition to the dance information, the volume also contains treatises in Latin on chiromancy (palm reading) and physiognomy (judgment of character from facial features), as well as a collection of Latin prayers.

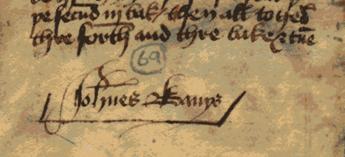

The attribution of the work to John Banys comes from the name appearing twice in the volume: at the end of the second gathering, and inside the back cover. The name is written in the same hand and with the same ink as the rest of the text. Fallows was not able to find references to Banys in historical documents, but notes in the back cover make reference to a “Mr. Rauff Shyrley of Stanton”. The Shirleys were a well-known family in southern Derbyshire, and a Ralph Shirley headed the family around the time of the volume (he married in 1496, died in 1517, but lived in Shirley rather than Stanton).

Steps

The 26 dances described in the notebook share a common style and step vocabulary. The casualness of the descriptions implies that Banys was familiar with a set of practices and steps common to the repertoire. Unfortunately, Banys does not record these, so we are forced to read between the lines to determine what some of the terms may mean.

In some cases, there are obvious parallels to contemporary continental steps. The brawle sounds like the basse danse branle, and the torne echoes the Italian volta.

Other steps, however, do not have obvious counterparts. The step flowrdilice sounds like fleur-de-lis, but what does the dancer do to accomplish this? The instruction is given sometimes to multiple dancers, and at other times to a single dancer. Similarly, the rak step requires some interpretation and research.

Another open question is the nature of the opening sequence of the dances. Most of them are notated “with trace”, “trace”, or “doble trace” after the title, and many descriptions begin with “After the end of the trace”. Three dances have descriptions of steps before “After the end of the trace”, but there is no obvious pattern by which to extend the different sets of steps to the other dances.

Music

Like many dance sources, the notebook contains only melody lines for the music. Nevile in her 1999 paper explores the structure of the music. She finds no pattern to the repeat schemes used, or to the lengths of musical phrases. She concludes that the music and dances are tightly coupled. The tunes do not follow the structure of the basses danses, with a single note length throughout, but rather vary their rhythms. Mensuration changes for some of the dances, which opens the question of whether the different sections would have been performed differently.

|

John Banys’ signature from page 69 of the notebook.

At right, 16th century brass monument of an unknown Tudor couple from St. Peter's Church in Brown Candover, Hampshire.

|

|

England 1500

· 1485-1509. Henry VII is King of England. He restores a strong central government, promotes trade, and avoids foreign wars.

· 1500. Black “lead” pencils, composed of graphite mixed with clay, are introduced.

Social Context

Little definite is known about the state of dance in England during the early Tudor years. Jennifer Nevile presented some information in her 1998 paper. Citing Streitberger, she says that accounts of the Revels Office collected during this time contain references to “mores daunces”, several “baas dances” in 1501, and a “pabana” in 1522. The revels “subsumed a variety of forms, including the pageant, the mummery, the morris, the tourney, barriers, the disguising, the play, and the mask.” They “depended upon variety, and variety in the disguising depended on elaborate costuming and intricate dancing.”

In 1494, the Twelfth Night celebration “included a disguising of 12 gentlemen and 12 ladies.” The ladies were described as dancing “very demurely, with no violent gestures or movements to disturb their limbs,” whereas the gentlemen “progressed down the hall leaping and dancing”, and after unmasking continued “for an hour, performing ‘lepys Ganbawbys & turningys’ above the ground ‘which made that theyr spangyls of goold & othyr of theyr Garnyisshys ffly ffrom theym Ryght habundantly’”. Nevile observes that lepes in the dances in the notebook only occur in dances which are specifically for men.

In 1999, Nevile explores the names of the dances. Many are names of English families who would have been well known in the late fifteenth century. She suggests that “Kendall could refer to John Kendall, secretary to Richard III […] who was killed fighting for Richard at Bosworth field.” She also notes that “Talbot was the family name of the Earls of Shrewsbury, and Mowbray the family name of the Dukes of Norfolk.” The later Italian sources regularly dedicate dances to the nobility of the time, and it may be that this practice was also followed in England.

Sample Dance: Esperans

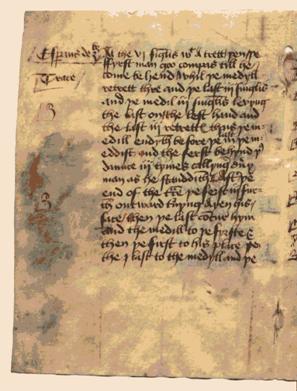

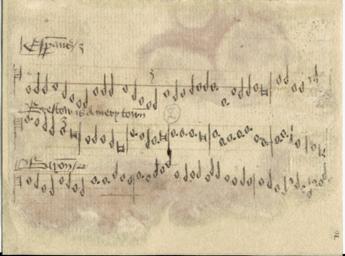

Esperans is the first dance described in the manuscript, and one of the few dances with accompanying music. The illustration below is the first page of the description of Esperans, taken from the cd-rom facsimile issued by the Derbyshire County Council. The text of the dance follows; the transcription is from David Fallows’ article in the RMA Research Chronicle.

Esperans de tribus: Trace. All the 6 singlis with a trett. Then the fyrst man goo compas till he come behend, whil the medyll retrett thre, and the last 3 singlis, and the medil 3 singlis, levyng the last on the left hand, and the last 3 retrettes. Thus the medill endyth before the last in the meddist and the ferst behynd. Thus daunce 3 tymes, calling every man as he standdith.

After the end of the trace, the ferst 3 furth outward turnying ayen his face. Then the last contur hym, and the medill to the fyrste; and then the first to his place.

Then the last to the medyll and the medyll to the last mans place.

The first and last chance place whil the medyll tornyth.

Al at onys retrett 3 bake. Bak al at ons.

Then the first turne whill the last turne in (in) his own place.

Then al togeder thre furth.

|

|

Above, the music for Esperans and Bayonn from John Banys’s notebook At left, the instructions for Esperans

|

Primary Source

Matlock, Derbyshire Record Office D77 box 38 (Gresley). Facsimile: Derbyshire County Council and Document Control Services. John Banys’ Medieval Dance Notebook. cd-rom facsimile.

Additional Sources

Fallows, David. “The Gresley Dance Collection”. In Royal Musicological Association Research Chronicle, 29, 1996.

Neville, Jennifer. “Dance Steps and Music in the Gresley Manuscript”. In Historical Dance, 3.6, 1999.

Webb, Cait. Eschewynge of Ydleness: Steps for Dancing. Manual with reconstructions.

Wilson, David. “Performing Gresley Dances: the View from the Floor”. In Historical Dance, 3.6, 1999.

Recordings

Eschewynge of Ydleness. Misericordia and Gaita. Available from www.gaita.co.uk/cd.html

A Consort of Dances, Dragon Scale Consort. Music for one dance (Ly Bens)

Arbeau’s Orchesography

For dancing is practised to reveal whether lovers are in

good health and sound of limb, after which they are permitted to kiss their

mistresses in order that they may touch and savour one another, thus to

ascertain if they are shapely or emit an unpleasant odour as of bad meat.

Therefore, from this standpoint, quite apart from the many other advantages to

be obtained from dancing, it becomes an essential in a well-ordered society.

-Arbeau

About the Source

Orchesography is presented in the form of a dialogue between a dance master and a law student who desires to learn more of the noble art of dance, for a knowledge of dance “render[s] one’s company welcome to all.” This dialogue provides a wealth of information about the place of dance in 16th century society, as well as providing invaluable details on the dances themselves. The tabulation for each dance includes a basic melody line running vertically along the page, with the steps written next to it, carefully aligned with the notes. Thus it is clear how long each step takes to perform, and which part of the music each step lines up with. Another valuable aspect of Arbeau’s work is that drawings of dancers executing each step accompany the textual descriptions of those steps, helping to ensure accurate reconstructions, and each dance is carefully described and tabulated.

Music

Arbeau provides a basic tune for each type of dance, which often can be found in a four-part setting in other period sources, including those published by Attaignant, Susato, Moderne, and Phalèse.

The pavan, Arbeau’s basse dance, and the majority of the branles are in duple time. The galliard, tordion, and lavolta are danced in triple time, with a characteristic ¾ (or 6/4) rhythm with a strong accent on the fourth beat, which emphasizes the pattern of the dance steps.

Dance music could be played by a single musician, playing both tabor (drum) and flute; however, Arbeau states that there “is no workman so humble that he does not wish to have hautboys and sackbuts at his wedding.” Pavans and basses could be played on violins, spinets, flutes, and hautboys, with the tabor’s rhythm providing “an immense help in bringing the feet into the correct positions.

Dances

Within the SCA, Arbeau’s work is best known for branles, the pavan, and galliarde. Although the branle as a well-known form of dance remained in vogue for over two hundred years, Arbeau’s descriptions are the single best resource we have for learning how these dances were performed.

He includes instructions for 23 different branles, giving us a varied and enjoyable repertoire of this form of dance. Branles were done as a line, the ends of which could be joined to form a circle. Arbeau says “When you begin a branle, several others join hands with you, as many young men as damsels: and sometimes she who is at the last to arrive at the dance, takes your left hand, & thus makes a round dance.” If the branle was danced as a line, the person at the far left end was the leader of the line, and this appears to have been an honored position to hold.

Arbeau’s pavan is quite simple, being made up of two singles and a double forward and two singles and a double backward, or, if the dancers did not wish to move backwards, the pavan could instead proceed forward, circling the room two or three times. Arbeau discusses the galliarde (and its variants, lavolta and tordions) in detail; these are also discussed in Caroso and Negri.

Arbeau also includes brief looks at several dances which are covered in more detail in other sources, including: the Alman, the Coranto, Canaries, Basse Dance, and Morris Dance. His treatise ends with an in-depth discussion of Bouffons or Buffens, a sword dance with costumed dancers, meant to be performed as part of a masque.

The position of partners took in relation to each other is shown in Arbeau, both through illustrations and text, as the lady on the gentleman’s right, her left hand resting palm down upon his right hand. Their arms are relaxed at their sides, with hands held at waist level.

|

|

These illustrations from Arbeau show the reverence and a capriole, or moving of the feet in the air during a large jump. Capriol also happens to be the name of the student in the dialogue. In addition to showing us the right foot and body positions, the illustrations show what costume is appropriate. At left, Portrait of a Lady. French, painted 1570-5. This painting shows some additional detail for costume of this period. |

France 1589

· 1589. Catherine de Médicis dies at age 69. She was the daughter of Lorenzo de Médicis. She was queen consort of Henry II, then later regent for her son Charles IX.

· 1589. Henri of Navarre becomes King of France, beginning the House of Bourbon, after Henri III is murdered by a Dominican monk at St. Cloud outside Paris.

Social Context

Arbeau perceived dance as “a pleasant and profitable art which confers and preserves health; proper to youth, agreeable to the old and suitable to all provided fitness of time and place are observed.” He implies that people of all ages and all social classes participated. We can infer that the dances he described were suitable to his own social class, the educated upper middle class. He states “the pavan is employed by kings, princes, and great noblemen,” while the Haut Barrois “is danced by lackeys and serving wenches, and sometimes by young men and damsels of gentle birth in a masquerade.” He recommends dance for young girls and discusses the influence of “wise and dignified matrons” on the fashion in dance.

Arbeau says that “Musicians are all accustomed to beginning the dances at a feast” with a certain Suite of branles, which are performed by various groups: “the elderly solemnly dance the double and single branles; the young married dance the gay branle; and the youngest of all lightly dance the Burgundy branle.” When dancing at a feast was begun with a suite of branles, it appears that all the guests joined in. Mersenne writes, in describing his Suite: “There are six kinds [of branles] which are danced now-a-days at the opening of a Ball, one after the other, by as many persons as wish; for the entire company, joining hands, perform with one accord a continual branle...”

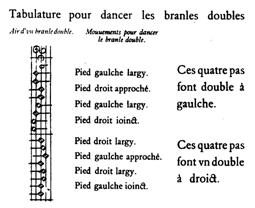

Sample Dance - Double Branle

Arbeau’s description of this dance is very detailed, as this is the first branle covered in Orchesography.

Since you already know how to dance the pavan and the basse dance it will be easy for you to dance branles in the same duple time, and you should understand that the branle is danced by moving sideways and not forward. To begin with, in what is called the double branle you will perform one double to the left and then one double to the right; you are well aware that a double consists of three steps and a pieds joints. To perform these sideways, you will assume a proper bearing after the révérence of salutation, and, while keeping the right foot firmly in position, throw your left foot out to the side which will make a pieds largis for the first bar. Then for the second bar, keep the left foot firmly in position, bringing the right foot near to the left which will make a pieds largis that is almost a pieds joints. For the third bar, keep the right foot firm and throw the left foot out to the side which will make a pieds largis, and for the fourth bar keep the left foot firm and bring the right foot close to it which will make a pieds joints. These four steps, made in four bars or tabor rhythms, we shall call a double à gauche, and you will do the same in the opposite direction for a double à droit. Namely, while keeping the left foot firmly in position you will throw the right foot out to the side, which will make a pieds largis for the fifth bar. Then for the sixth bar keep the right foot firm and bring the left foot near to the right, which will make a pieds largis that is almost a pieds joints. For the seventh bar, while keeping the left foot fast, you will throw the right foot out to the side, which will make a pieds largis. Finally, for the eighth bar, you will keep the right foot fast and bring the left foot close to it, which will make a pieds joints, and these last four steps we call double à droite. And thus, in these eight steps and bars the double branle will be accomplished as you will see in the tabulation, and you will repeat from the beginning making a double à gauche and then a double à droite.

|

|

This tabulation, from the Fonta reprint, shows the alignment of steps with the music. For many dances in Arbeau, the tabulation is the main reference for the dance. In the case of this dance, Mary Stuart Evans’ translation above shows the patience of Arbeau’s description. |

Primary Source

Arbeau, Thoinot. Orchesographie. Lengres, 1589. Facsimile at Library of Congress website, linked from http://www.rendance.org/primary.html. Facsimile of 1888 Fonte reprint, Forni, 1981. Translation by Mary Stewart Evans with notes by Julia Sutton: Dover, 1967.

Recordings

New York Renaissance Band. Orchesographie. (aka Washerwomen, War, and Pease) Arabesque Recordings, Z6514, 1984.

Broadside Band. Danses Populaires Françaises & Anglaises. Harmonia Mundi, HMC 901152, 1984. Very pretty, very danceable to, but some dances are a little slow.

Several dances from Arbeau appear on the cross-genre recordings listed at the end of this article.

Caroso and Negri

[Knowledge of dancing] is so essential to one of good

breeding, that when it is lacking it is considered a fault worthy of

reproof. As a result of dance many other praiseworthy and honourable

qualities may be acquired, for through physical exercise one keeps fit and

becomes agile and dexterous; one also learns proper deportment... required by

etiquette and ceremony. In sum, dance conjoins grace, beauty, and decorum

in the eyes of the beholder.

-Caroso

About the Sources

Fabritio Caroso and Cesare Negri were dancemasters to the courts of Italian nobility in the last half of the 16th century.

Caroso’s volumes include Il Ballarino, published in Venice in 1581, and Nobiltà di Dame, published in Venice in 1600, reprinted in 1605, and under a different title in 1630.

Negri’s work, Le Gratie d’Amore, was published in Milan in 1602, and re-issued under a different title in 1602 and 1604. A manuscript translation into Spanish was done in 1630.

These are elegant books, with ornate title pages, several colophons showing initial positions for the dances, and decorative capitals throughout. They each contain a treatise on steps, style, and etiquette, followed by choreographies of dances with accompanying music. They are clearly written for the upper classes, and incude detailed instructions regarding the behavior of and toward princes and princesses.

Music

The music is notated in Italian lute tablature, which shows the sequence of strings and frets played. Some dances are also accompanied by a separate melody in mensural notation.

Rooley (Early Music, 1974) states the music has only a simple tune (e.g. an 8 bar strain), intended to be repeated endlessly, and the barest harmonic framework for support. This suggests the player of the melody instrument (e.g. cittern or lute) improvised constantly changing divisions.

|

|

The opening position for Contentezza d’Amore, in Nobiltà di Dame. Caroso advises gentlemen: “Be careful never to dance without your cape, because this looks most unsightly... when a gentleman wears a sword while dancing these lively dances, he should hold it with his left hand, so that it will not wave around wildly... [when doffing the hat for a reverence] turn the inside of your bonnet toward the thigh.” He also includes advice for removing gloves when invited to dance. Ladies are advised on how to wear chopines properly, and how to manage their farthingales. |

|

Negri. From Le Gratie D’Amore. |

Dances

The choreographies of these dances are quite lengthy, and often verbose, but are essentially a series of step names linked by a number of stock phrases which indicate basic floor patterns, the direction of individual steps, and the presence of courtesy movements.

These dances are made up of a large number of steps, which are described in a varying manner throughout the sources: Il Ballarino contains 52 named steps, Nobilta has 67, and Negri’s Le Gratie d’Amore has two dozen. The emphasis in this period was on the footwork, which was vigorous, complex, skillful and speedy. Dances included familiar types, such as pavans, galliards, and corantos; miming dances; flirtatious balli which were effectively choreographed chases, and mixers in which dancers changed partners throughout the dance. Within all of the prescribed choreograpies, improvisation was highly regarded as skilled ornamentation of the dance. Negri’s work includes 70 pages of galliard variations.

Italy 1580-1602

· 1582. New Gregorian calendar adopted by Roman Catholic countries throughout Europe.

· 1591. Plague and famine strike Italian states.

· 1592. Galileo leaves Pisa after challenging the notion that objects fall at a rate proportional to their weight. He tested this by dropping cannonballs off the leaning tower.

· 1600. Italy’s population is 13 million.

Social Context

Within these sources, each dance is dedicated to a noble lady, and is preceded by a dedicatory poem extolling her virtues. The honored ladies include the Queen of France, the Queen of Spain, the Duchess of Mantua and so on. It is likely that many of ladies were not personally known by the authors, who may have included their names in order to flatter them (and possibly to gain favor with them in return). However, it is clear that the dancemasters of the time did frequently deal with royalty and were in the employ of young aristocrats training for important court occasions.

Caroso includes notes on conduct which shed light on numerous aspects of dance in his society: “When a prince or gentleman is invited to dance by a lady, it is improper for anyone else to take his [seat].” “It is the custom to invite cardinals to parties of importance (that is, for the nobility), and to seat them according to precedence: dukes, princes, marquises, counts, lords, and knights.” When inviting a gentleman to dance, it is best for a lady to look directly at her chosen partner “so that those sitting near to or behind him will not need to rise, thus avoiding any ensuing scandal. Now as he rises, the gentleman who she has invited should remove his right glove at the same time as she makes a Reverence to him, and and she should pretend to adjust her dress, making it sway.”

Sample Dance: Contentezza d’Amore

The name of this dance means “the contentment of love.” It appears in Il Ballarino, and then in Nobilta di Dame with corrections.

Below are the instructions for Contentezza from Nobilta di Dame; the translation by Julia Sutton of the first four sections is presented following.

|

|

|

|

Stand opposite each other holding both hands, as shown in the figure, and make a long Reverence in time to the music, with two breve continences. Then do two reprises, two falling jumps, and one breve sequence to the left; repeat to the other side. At the end, the gentleman drops the lady's right hand, in the usual courteous manner, and both make a Reverence as before, beginning everything with the left foot, and then with the right foot.

In the second playing, progress together holding hands (not as before, when the lady progressed first, and the gentleman afterwards, for I say that to dance it thus was quite wrong). You must, then, do two dreve stopped stepps together, with two semibreve steps and one breve sequence, beginning with the left foot; repeat to the other side, both the stopped steps as well as the other movements, beginning with the right foot. After this, turn to face towards each other at the other end of the ballroom, without dropping hands, and do two grave falling jumps, each in one beat, and three quick [falling jumps], in the time of two beats, beginning with the left foot. At the end do two breve continences, one with the left foot and the other with the right.

In the third playing, progress by doing the same passage to the other side, beginning with the right foot, and returning to the place where you began the dance.

In the fourth playing, take right hands and do two breve sequences, at the end of which drop hands in the usual courteous manner. Then turn to the left, with two more sequences, one going to one end of the ballroom, the other to the other end. This done, opposite each other, do two stopped steps, two more sequences flankingly, two grave falling jumps, and one dexterous step, beginning these movements with the left foot. Finally, do two stopped steps, as above.

Primary Sources

Caroso, Fabritio. Il Ballarino. 1581. Facsimile: Broude Bros., 1967. Facsimile at Library of Congress website, linked from www.rendance.org/primary.html Transcription: www.pbm.com/~lindahl/caroso/transcription/

Caroso, Fabritio. Nobiltà di Dame. 1600. Facsimile: Forni, 1980. Facsimile at Library of Congress website, linked from www.rendance.org/primary.html. Transcription: http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/caroso2/ Book with translation by Julia Sutton, includes modern music. Oxford University Press, 1986. Revised paperback edition titled Courtly Dance of the Renaissance from Dover, 1995.

Compasso, Lutio. Ballo della Gagliarda. 1560. Facsimile with intro and notes: fa-gisis, 1995. Transcription: http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/compasso/

Negri, Cesare. Le Gratie D'Amore. 1602. Facsimile. Broude Brothers, 1969. Translation by Gustavia Yvonne Kendall: University Microfilms International, 1985.

Santucci. Mastro del Ballo. 1614. Facsimile with extensive introduction: George Olms, 2004.

Additional Sources

Lehner, Markus. A Manual of 16th c Italian Dance Steps. fa-gisis, 1997. Compares descriptions of steps from several primary sources.

Wortelboer, Dorothee. Celeste Giglio: Flowers of 16th c dance. Manual. Tactus Music, 1996.

Recordings

The Broadside Band. Il Ballarino, Italian Dances c. 1600. Hyperion CDA66244. (Companion manual available from www.dhds.org.uk)

Ensemble la Follia. Le gratie d’Amore. Dynamic, 1997

Lacrimae Ensemble. Celeste Giglio. Erasmus, 1996. Companion to Wortelboer. Available from http://utopia.ision.nl/users/dorothee/lachrimae.htm

The Old Measures

About the Sources

The Old Measures are a collection of dances described in several informal sources spanning over a century. The sources that survive to describe the dances are not formal works, but rather notes discovered in the documents of people associated with the inns. These are: 1. the personal notebook of Eliner Gunter; 2. a sheet signed in 1594 by John Willoughbye of Devon; 3. a list of dances in a collection of miscellaneous papers by John Stowe and others; 4. a sheet entitled “Practise for Dauncing” in a collection by John Ramsay; 5. a “Copey of the oulde measures” written by a young Elias Ashmole, where he writes “Rowland Osborne taught me to dance these measures”; 6. a list of “The Measures as they are Danced in the Inner Temple Hall”, signed by Butler Buggins, who was Master of Revels of the Inner Temple in 1672- 5; and 7. a “Copy of the old Measures in the Inner Temple,” also signed by Buggins, which includes some music. The sources have significant differences in their text, but they do have common structure: six begin with the same seven dances in the same order.

Some of the sources are associated with the Inns of Court, four groups of buildings in London where English trial lawyers lived, studied, taught, and held court. In period, young aspiring lawyers came to the Inns to study law from lawyers who resided there. Since the 1400’s, the Inns sponsored revels for various holidays filled with singing, dancing, and other pastimes. In the 1600’s, Sir William Dugdale wrote: “Nor were these Exercises of Dancing merely permitted; but thought very necessary (as it seems) and much conducing to the making of gentlemen more fit for their Books at other times.”

Music

Of the seven sources, only one includes music, and that one only gives music for five dances. However, there are several contemporary sources which include settings for almans that can be adapted for use with these dances, and Pugliese-Casazza also includes modern music composed in a period style for one dance which has no extant music available.

The sources also do not indicate instrumentation, but Thomas Morley’s work from the same period would indicate that a consort of violin, flute or recorder, bass viol, lute, cittern, and bandora would be appropriate (Rooley, 1974). Alman music is typically in moderate imperfect time.

Dances

Many kinds of dance are described in the manuscripts. All seven sources include the Quadran Pavan and a number of almans. Corantos, galliards, a “Spanioletta,” and a description of “brawles” can also be found, though sometimes the descriptions aren’t as complete as might be desired. One source describes the cinquepace (galliard) as “One, two, three, four, & five,” and says that the Spanish Pavan “must be learnd by practise & demonstration, being performd with boundes & capers & in the ende honour.”

None of the sources include any description of the steps to be used. They call for doubles, doubles with hops, singles, slides, and set & turnes, but never detail how these steps are to be executed. Some modern researchers have chosen to use steps from the Italian repertoire of this period, but it is more common to adopt the steps described in Arbeau’s Orchesography. Arbeau describes an alman double step composed of three steps (forward or backward) and one grève, or pied en l’air without saut. (Evans, 125) A grève is the movement which “results when the dancer transfers his weight from one foot to the other while the foot previously on the ground is raised in the air in front of him.” (Evans, 87) A pied en l’air without saut (jump) is a smaller movement: “the foot is only raised slightly off the ground, and moved little, if at all, forward.” (Evans, 86)

|

|

Torch bearers lead a couple during a 1612 celebration. Note the arrangement of the spectators around three sides of the room; an official notice in the Middle Temple stated that “In the presenting and performance of revels, no gentleman of the House shall make use of the gallery over the screen, or bring down any lady or gentlewoman to see their ordinary Revels, or dance with them in the Hall in the absence of the Bench.” |

|

|

This contemporary picture shows two couples dancing, accompanied by a string consort. Note that the gentlemen are wearing capes and swords. One is wearing his hat; the other has removed it, perhaps for a reverence? The woman on the left has a slight train on her dress.

|

London 1570-1675

· 1558-1603. Queen Elizabeth reigns in England.

· 1599. Globe Theater opened. Shakepeare’s Henry V and Much Ado are written.

· 1600. Tobacco becomes a popular extravagance.

· 1603. London’s population reaches 210,000.

· Age of Exploration and Colonization: Charter of East Indian Company in 1600; settlement of Bermuda in 1612; founding of Jamestown, Virginia in 1607.

Social Context

Dances were a central point of the many revels held at the Inns of Court. On the First Grand Night of the Gray’s Inn Christmas celebration in 1594, “his Highness [the Prince of Purpoole] called for the Master of Revels, and willed him to pass the time in dancing: so his gentlemen-pensioners and attendants, very gallantly appointed, in thirty couples, danced the old measures, and then galliards, and other kinds of dances, revelling until it was very late.” And again, on the following January 3rd: “The Prince having ended his speech, arose from his seat, and took that occasion of revelling; so he made choice of a lady to dance withal; and so likewise did the Lord Ambassador, the Pensioners and Courtiers attending the Prince. The rest of the night was passed in these passtimes.” (Nichols, in Cunningham, 5)

Similarly, when Bulstrode Whitelocke was Master of Revels of the Middle Temple for Christmas 1628, “They began with the old masques [measures]; after that they danced the Brautes and then the master took his seat whilst the revellers flaunted through galliards, corantoes, French and country dances, till it grew very late.” (Cunningham, 8)

As the quotes above indicate, these dances appear to have been done by large groups of people; apparently in lines of couples. In Arbeau’s description of the alman, he says: “You can dance it in company, because when you have joined hands with a damsel, several others may fall into line behind you, each with his partner.” (Evans, 125)

Throughout the manuscripts, it is clear that dances were done in a prescribed order. Typically, the first seven dances (called the Old Measures) were: Quadran Pavan, Turkelone, Earl of Essex Measure, Tinternell, The Old Alman, The Queens Alman, and Madam Sosilia. In later manuscripts, Black Alman was added as the eighth dance.

By the early 17th century, the Old Measures were followed by Post Revells. Descriptions of some of these are also included in the sources— Galliards, Corantoes, and Branles. Although some of the sources also mention country dances, none are described.

Sample Dance: The Black Alman

This dance appears in all but the earliest of the sources as the eighth old measure; it’s also the only alman for which music appears in the primary sources. Along with Madam Sosilia, it’s one of the more complex dances from the Inns.

8th. The Black Almaine. Sides 4 doubles round about the house and Close the last Double face to face then part yr hands and go all in a Double back one from the other and meet a Double againe Then go a Double to yr left hand and as much back to your right hand, then all ye women stand still and the men set & turne, then all ye men stand still and the women set and turne, then hold both hands and change places with a Double and slide four french slides to the mans right hand, change places againe wth a Double and slide four french slides to the right hand againe, Then part hands and go back a Double one from another and meet a Double againe. Then all this measure once over and so end.

The second all the men stand still and the women begin set and turne and then men last.

|

|

This music for the Black Alman appears in the “Copy of the old Measures” with the instructions above, transcribed by Cunningham. |

Primary Sources

1. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson Poet. 108. 1570

2. Somerset Records Office, DD/WO 55/7, item 36. 1594.

3. London, British Library, MS Harleian 367. 1575-1625

4. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 280. circa 1606

5. Oxford, Bodleain Library, MS Rawlinson D 864. c. 1630

6. London, Inner Temple Records, “Revels, Foundlings, and Unclassified, Miscellanea, Undated, &c.” v27. 1672-75

7. London, Royal College of Music, MS 1119. circa 1675

Additional Sources

Cunningham, James P. Dancing in the Inns of Court. London, Jordan & Sons, 1965.

Contains background information, quotes, and transcriptions.

Durham, Peter & Janelle. Dances from the Inns of Court. Redmond, WA, by the authors, 1998.

Includes historical background, reconstructions of steps and dances, and a concordance of the sources.

Payne, Ian. The Almain in Britain. Ashgate, 2003.

Sheet music: http://mysite.verizon.net/vzeryeh4/dancemusic/oldmeasures/OldMeasures.html

Wilson, D. R. “Dancing in the Inns of Court.” In Historical Dance, vol. 2, No.5, 1986-87.

A new transcription, which corrects some errors in Cunningham.

Recording

Jouissance. Dances from the Inns of Court. The companion CD for the pamphlet of the same name above. Available from Trahaearn; email trahaearn@msn.com.

English Country Dances

About the Source

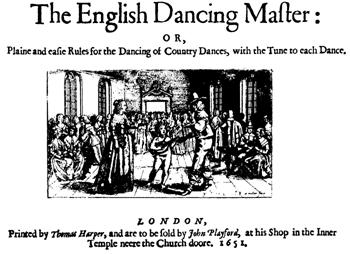

John Playford was a music publisher and bookseller living in London in the mid-seventeenth century. In March of 1650 (old style; what we call 1651), Playford published The English Dancing Master. This was a collection of 105 country dance tunes, and basic written directions of the figures to be performed to each tune. Playford himself probably did not write any of the dances, but instead gathered them from a number of contributors. Between 1651 and 1728, Playford and his successors published 23 editions of The Dancing Master.

Generally, each page of the text contains one dance. The title is accompanied by a written description of the formation of the dance (circle, square, etc.) and a diagram of the same. This is followed by a line of music for the melody of the dance, and by a textual description of the figures of the dance. The figures are divided into blocks of text which line up with repeats of the music, and this division is made clearer by the use of the following symbols within the dance description:

1 Stands for a straine playd once.

2 Stands for a straine playd twice.

3 Stands for a straine playd thrice.

Music

The tunes in Playford vary somewhat in style and complexity, due to diverse origins. Some appear to have been popular ballads to which dance steps were later set, some may have had their origin in earlier dances (e.g. Mundesse can be traced back to a basse dance in Susato’s Danserye of 1551), and some may have been written specifically for the dance associated with them.

Versions of the dance music appear in several contemporary sources, and include settings written for a variety of instruments, including keyboard, lute, cittern, recorders, lyra-viol, and flageolet.

Dances

Playford’s dances were performed by couples in certain set formations, such as: a square for eight, longways for six, and round for as many as will. He calls out the formation at the beginning of the dance description, and includes symbols to further clarify the set.

The most typical dances are made up of 3 verses, each followed by a chorus, which may or may not be the same throughout the dance. Some figures are simple, others are complex, as can be seen in the sample dances. In later editions, the popularity of most of the formations faded out to be replaced by almost exclusive use of the “Longways for as many as will.”

Most modern country dancers believe that these dances were meant to be light and lively, with a smooth flow of the steps from one figure to another, with the dancer constantly in motion.

Steps

It should be noted that Playford’s describes very few of the steps that make up the dances. He says only:

“A Double is four steps forward or back, closing both feet.

A Single is two steps, closing both feete.

Set and turne single, is a single to one hand, and a single to the other, and turne single.”

Because of the lack of detail here, modern researchers have searched through other period sources (including Arbeau and Feuillet) for clues to the performance of these steps. See the TI article and other modern sources for information on steps. In general; however, the dance steps are assumed to be fairly basic walking steps, with the main emphasis of the dance on the figures rather than on ornamented footwork.

|

|

The cover from Playford’s first edition. Note the angelic musician, and intermixing of men and women who are not dancing. The presence of only one couple seems unusual since all dances in this edition call for multiple couples.

|

London 1651-1728

· 1651. Charles II crowned on January 1. Oliver Cromwell takes Perth in August. A disguised Charles escapes to France October 17. Virginia colony receives influx of Cavalier (Royalist) refugees from England.

· 1651. London's population reaches 350,000, and the city contains 7% of the English population.

Social Context

Country Dances came into vogue at the end of the 16th century, when Queen Elizabeth, an avid dancer, became fond of them. “Almost every night she is in the presence, to see the ladies daunce the old and new country dances.”

However, despite the fact that several references are made to country dance as far back as 1560, even dances with names which later appear in Playford, there is little concrete information about how they were danced. An example is Sellinger’s Round, mentioned in 1593, 1600, 1604, and 1631. A description first appears in the third edition Playford (1657) as a dance that was “either round, or longways for six.” In the fourth edition (1670) it appeared again, but it gained a figure, and a formation of “round for as many as will”.

Playford’s country dances were probably done in a variety of social settings. They were almost certainly among the dances performed at the Inns of Court: evidence includes both the Lansdowne manuscript, and the fact that Playford himself dedicated the first edition and subsequent editions to “the Gentlemen of the Innes of Court.”

The place of English country then was perhaps not so different from today; several references imply country dances were the wilder and more energetic dances done by young people after the solemn dances were done. In 1626, a French ambassador wrote “After supper the king and we were led into another room… where there was a magnificent ballet… and afterwards we set to and danced country-dances till four in the morning.”

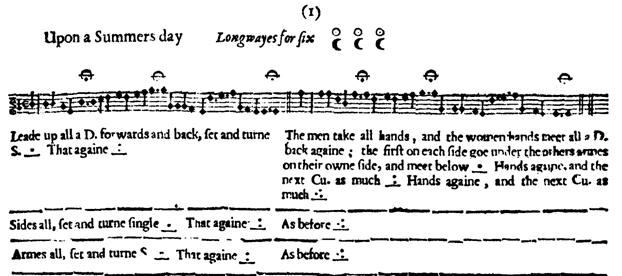

Sample Dance: Upon a Summer’s Day

This is the first dance in the first edition of Playford; it is one of the easier ones and makes a good first country dance.

Upon a Summers Day Longways for six

Leade up all a D. forwards and back, set and turn. S 1

That againe 2

The men take all hands, and the women hands meet all a D. back againe; the first on each side goe under the others armes on their owne side, and meet below 1 Hands againe, and the next Cu. as much 2 Hands againe, and the next Cu. as much 3

Sides all, set and turne single 1 That againe 2

As before 3

Armes all, set and turne single 1 That againe 2

As before 3

Primary Sources

Playford, John. The English Dancing Master. Modern edition edited by Hugh Mellor in 1933. London: Dance Books Ltd., 1984. Facsimile edition edited by Margaret Dean-Smith. London: Schott & Co., 1957. Facsimile: http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/playford_1651/ Transcription: www.contrib.andrew.cmu.edu/~flip/contrib/dance/playford.html

British Museum Library MS Sloane 3858. 17th or 18th c.

Includes 10 dances, most of which are in 1st edition Playford.

British Museum Library MS Lansdowne No 1115. c. 1648.

Written by a lawyer at the Inns of Court, describing dances done there. In Cunningham. 4 dances, 3 similar to early Playfords.

Additional Sources

Keller, Kate Van Winkle, and Genevive Shimer. The Playford Ball. Pennington NJ: A Cappella Books, 1990.

Keller, Robert. The Dancing Master: 1651-1728. Colonial Music, 2000. CD-Rom with indexes, images, and figure descriptions of all the dances from all the editions of Playford.

Sharp, Cecil J. The Country Dance Book, volumes 1-6. (Part 1 first published in 1902. Reprint: H. Styles, 1985).

Recordings

Country Dances. The Broadside Band. Harmonia Mundi, HM 40.1109.

The English Dancing Master. Orange and Blue. Available from www.cdss.org

Source Citations for Text and Pictures

Domenico and Students

Painted miniature of three dancing figures from Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, f. Ital. 973, c. 21v.

Six Principle Elements of Dance taken from Sparti’s translation, pages 93-100.

Dancers outdoors [uncaptioned] from the engraving The Planet Venus, British Museum. Printed in Sparti.

Details of the 1459 festival are quoted from Smith’s translations of Florence B.N.C. Magl. VII.1121 and Galeazzo’s account written on April 30, 1459 in Milano, Archivio di Stato. The competition detail is also Smith’s translation. The description of the moresche is from Cod. Palat. 286 in Florence, as quoted in Sparti, page 55.

Burgundian basse danses

Step descriptions and general rule for mesures are quoted from the translation by Kronenfeld and Gill.

Quote on purpose of basse dance from Gavenda, in his 1988 introduction to Brussels manuscript.

A courtly couple dance. From the Freydal of Maximillian I, c. 1502-1512. Vienna, Nat. Bibl., ms. 2831. From Heartz.

John Banys’ Notebook

Brass image from Trivick, Henry. The Picture Book of Brasses in Gilt. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971, as reproduced on “Tudor dress portfolio of images” at http://www.uvm.edu/~hag/sca/tudor/

Revels Office notes are from Streitberger, W.R, Court Revels, 1485-1559, Toronto, 1994.

Image of page 54 from the Derbyshire County Council cd-rom facsimile, p. 57.

Transcription of Esperans from Fallows, p. 7.

Arbeau’s Orchesography

Translations of Arbeau, including quotations, from the Mary

Stewart Evans translation.

Portrait of a Lady, from Microsoft Art Gallery. © 1993 The National Gallery,

London.

Caroso and Negri

All text translations from Sutton.

The Old Measures

Transcriptions from the Inns of Court manuscripts are from Cunningham.

Picture of two couples dancing, from Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Douce E.2.6.(311). Printed in Early Music, Feb 1986.

Picture of Morocco and trainer, from John Dando, “Maroccus extaticus, or Banks’ Bay Horse in a Trance”, 1594. Printed in the Riverside Shakespeare, 1972.

Picture of torch bearers and couple is a detail from an engraving by J. T. Bry in the British Museum.

Quote regarding the gallery is C. T. Martin, Minutes of Parliament in the Middle Temple, 1904-5, quoted in Cunningham, p. 19.

English Country Dances

Quote from French ambassador, quoted in Cunningham, page 16.

Quote about Queen Elizabeth from 1600. It appears in Cunningham, page 15.

Helpful Sources which cover multiple genres

Publications and Online Resources

Durham, Peter and Janelle. Western Dance: 1450 – 1650. Compleat Anachronist #101. Society for Creative Anachronism, 1999. Dance manual which includes step reconstructions, and choreographies for representative dances from each genre. (Each reconstruction includes original period text descriptions of the dance, and notes on where to find good recorded music).

Elson, David. Del’s Dance Book. Available online at www.sca.org.au/del/ddb/ For each genre of dance, includes introductory material, step reconstructions, and choreographies for several dances. Also includes links to sheet music, and links to annotated bibliographies, which link to online sources for facsimiles, transcriptions, and translations.

Letter of Dance. SCA dance publication. Archives available online: www.pbm.com/~lindahl/lod/

Recordings

Companions of St Cecilia. 1990. Available as MP3 at http://sca.uwaterloo.ca/CD-offer/

Courtly Dances of Western Europe 1450 – 1650. Jouissance, 1999. Order from Trahaearn@msn.com Companion to Durham, above.

Dolmetsch Historical Dance Society has a large collection of danceable CD’s: www.dhds.org.uk

Musica Subterranea. Order at http://www.musicasub.org/

Tape of Dance. Accompany Letter of Dance. Download at http://sca.uwaterloo.ca/CD-offer/